Aphrodite

Two Bathers

Under The Olive Tree

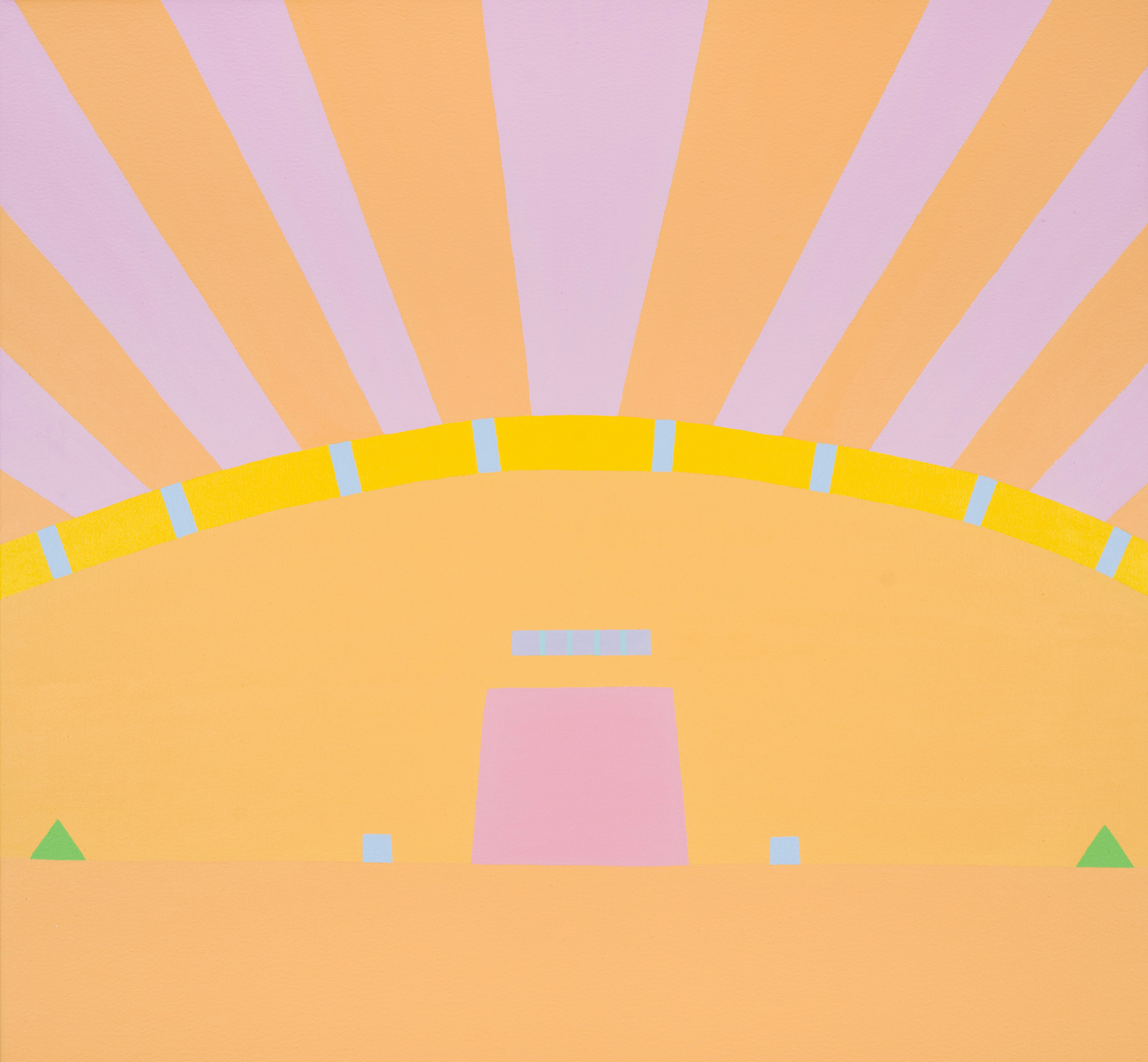

The Caravan Passed This Way

Untitled (Dervish Tower)

Two Bathers

Under The Olive Tree

The Caravan Passed This Way

Untitled (Dervish Tower)

Melina Cultural Centre, Athens.

4 December 2021 – 23 January 2022

There are no shadows in Charles Howard’s paintings – they are conquered by light. If we accept that ‘beauty is a battle – the triumph of light over shadow’, according to Jacques Lacarrière’s Dictionary of the Lover of Greece,[i] Howard’s paintings most eloquently illustrate this battle – the essence of beauty.

In Skyrian Hasapiko (1972), the oldest work on display, the lamplight shines on most of the painting, spotlighting thescene. Under this interrogation-like light source, a watchful eye, a ritual zeibekiko dance unfolds, exuding manliness, a mystical ascension, Dionysian ecstasy – a ‘solitary lament.’ Howard’s painting captures a stereotypical image, reminiscent of Alexis Damianos’s Evdokia (1971) and Lacarrière’s Greek Summer (1975). To quote the French author once again, Howard’s figures have ‘the immobility of marble.’ In this case, the dancer’s ritualised pose – frozen in time– is evidence that ‘in Greece, time, history, continuity have been just a long, still, contemplative gaze.’[ii]

In his art, Howard venerates women – women in the Greek landscape, to be precise. Female figures, typically nude or semi-nude, dominate his paintings, set against a backdrop of sea and barren mountains – the essence of Greek summer. These portraits of women are set in a plain landscape which is sometimes punctuated by one or two islands, there to suggest that these, mostly nameless, women are captured in moments of carefree abandon and reverie. In these portraits, Howard accentuates feminine facial features (feline eyes, brightly coloured lips), treating a woman’s face as if it were an exotic landscape. The strong women of the rebetiko world and the figure of Aphrodite prevail in his paintings. The former bring to mind Mortissa Hassiklou (1933), the well-known rebetiko song by Markos Vamvakaris; the latter evokes the ‘pure figure of Desire’, which is ‘living proof that the human body is the fountain of life and the jewellery box of the flesh.’[iii]

The portraits that make up Greek Summer are complemented by paintings inspired by the East, specifically by Islamic art and architecture. Some of them, such as The Gift (2003), are of a narrative kind. Yet most – especially those of the last decade – are abstract; their titles refer to places and countries – Misir (Egypt), Yazd (the Iranian city), Saray (a Turkish palace). Here Howard experiments with vivid colours and their illusionary nature, in a manner reminiscent of the works of Op Art, but also of the theory of Johannes Itten and Josef Albers about the interaction of colour. It is no accident that these small-scale, square-shaped works look like ceramic tiles: In a way, they make up the mosaic of a delightful style of painting inspired by personal experiences and memories of places.

Howard’s paintings bring to mind the French cartoonist Jacques de Loustal – the eroticism of his images, their sweet insouciance. Indeed, Howard could very well be a comic book artist with a painterly style – one, in fact, who has also got a remarkable body of paintings to show. Inversely, he could be a painter who has been strongly influenced by comics or a painter who has influenced comic book artists. In any case, if there is one take-away from Howard’s paintings (in which figures and landscapes exist in perfect harmony), it is love – love for Greece, love for specific persons, places, and cities, such as the bewitching Istanbul, where he spent a considerable part of his life: ultimately, love for life. These images suggest that their author lived a rich and happy life. Charles Howard passed away last September after a life full of experiences, leaving behind a body of work that glows with vitality and kindles positive emotions. With this exhibition, Greece reciprocates his love.

Translation: Dimitris Saltabassis

[i] Jacques Lacarrière, Dictionnaire Amoureux de la Grèce, Plon, Paris 2001 (in French); Greek edition: Ερωτικό Λεξικό της Ελλάδας, Harris Papadopoulos, Ioanna Hatzinikoli et al. (transl.), Nefeli, Athens 2020, p.355.

[ii] Jacques Lacarrière, L'été grec. Une Grèce quotidienne, Plon, Paris 1976; Greek edition: Το Ελληνικό Καλοκαίρι. Μια Καθημερινή Ελλάδα 4000 Ετών, Ioanna Ηatzinikoli (transl.), Ηatzinikoli 1980, p.13.

[iii] Lacarrière, Ερωτικό Λεξικό, p.76.

4 December 2021 – 23 January 2022

There are no shadows in Charles Howard’s paintings – they are conquered by light. If we accept that ‘beauty is a battle – the triumph of light over shadow’, according to Jacques Lacarrière’s Dictionary of the Lover of Greece,[i] Howard’s paintings most eloquently illustrate this battle – the essence of beauty.

In Skyrian Hasapiko (1972), the oldest work on display, the lamplight shines on most of the painting, spotlighting thescene. Under this interrogation-like light source, a watchful eye, a ritual zeibekiko dance unfolds, exuding manliness, a mystical ascension, Dionysian ecstasy – a ‘solitary lament.’ Howard’s painting captures a stereotypical image, reminiscent of Alexis Damianos’s Evdokia (1971) and Lacarrière’s Greek Summer (1975). To quote the French author once again, Howard’s figures have ‘the immobility of marble.’ In this case, the dancer’s ritualised pose – frozen in time– is evidence that ‘in Greece, time, history, continuity have been just a long, still, contemplative gaze.’[ii]

In his art, Howard venerates women – women in the Greek landscape, to be precise. Female figures, typically nude or semi-nude, dominate his paintings, set against a backdrop of sea and barren mountains – the essence of Greek summer. These portraits of women are set in a plain landscape which is sometimes punctuated by one or two islands, there to suggest that these, mostly nameless, women are captured in moments of carefree abandon and reverie. In these portraits, Howard accentuates feminine facial features (feline eyes, brightly coloured lips), treating a woman’s face as if it were an exotic landscape. The strong women of the rebetiko world and the figure of Aphrodite prevail in his paintings. The former bring to mind Mortissa Hassiklou (1933), the well-known rebetiko song by Markos Vamvakaris; the latter evokes the ‘pure figure of Desire’, which is ‘living proof that the human body is the fountain of life and the jewellery box of the flesh.’[iii]

The portraits that make up Greek Summer are complemented by paintings inspired by the East, specifically by Islamic art and architecture. Some of them, such as The Gift (2003), are of a narrative kind. Yet most – especially those of the last decade – are abstract; their titles refer to places and countries – Misir (Egypt), Yazd (the Iranian city), Saray (a Turkish palace). Here Howard experiments with vivid colours and their illusionary nature, in a manner reminiscent of the works of Op Art, but also of the theory of Johannes Itten and Josef Albers about the interaction of colour. It is no accident that these small-scale, square-shaped works look like ceramic tiles: In a way, they make up the mosaic of a delightful style of painting inspired by personal experiences and memories of places.

Howard’s paintings bring to mind the French cartoonist Jacques de Loustal – the eroticism of his images, their sweet insouciance. Indeed, Howard could very well be a comic book artist with a painterly style – one, in fact, who has also got a remarkable body of paintings to show. Inversely, he could be a painter who has been strongly influenced by comics or a painter who has influenced comic book artists. In any case, if there is one take-away from Howard’s paintings (in which figures and landscapes exist in perfect harmony), it is love – love for Greece, love for specific persons, places, and cities, such as the bewitching Istanbul, where he spent a considerable part of his life: ultimately, love for life. These images suggest that their author lived a rich and happy life. Charles Howard passed away last September after a life full of experiences, leaving behind a body of work that glows with vitality and kindles positive emotions. With this exhibition, Greece reciprocates his love.

Christoforos Marinos

Art Historian

OPANDA curator of exhibitions and events

Translation: Dimitris Saltabassis

[i] Jacques Lacarrière, Dictionnaire Amoureux de la Grèce, Plon, Paris 2001 (in French); Greek edition: Ερωτικό Λεξικό της Ελλάδας, Harris Papadopoulos, Ioanna Hatzinikoli et al. (transl.), Nefeli, Athens 2020, p.355.

[ii] Jacques Lacarrière, L'été grec. Une Grèce quotidienne, Plon, Paris 1976; Greek edition: Το Ελληνικό Καλοκαίρι. Μια Καθημερινή Ελλάδα 4000 Ετών, Ioanna Ηatzinikoli (transl.), Ηatzinikoli 1980, p.13.

[iii] Lacarrière, Ερωτικό Λεξικό, p.76.