Aphrodite II

Hijaz

Untitled (Orange Tower)

Smack (A Portrait of Elvie Thomas)

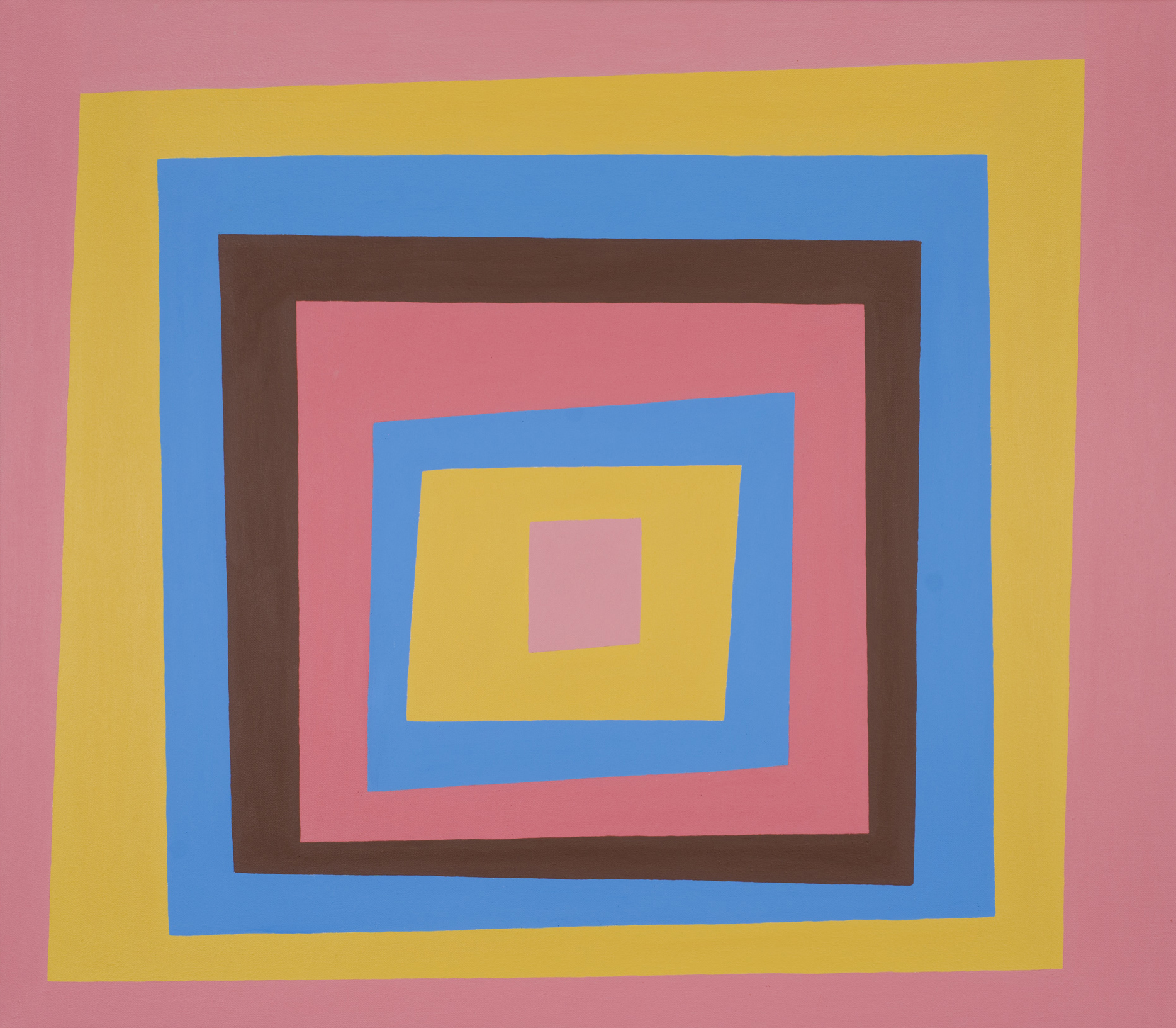

Knossos

Hijaz

Untitled (Orange Tower)

Smack (A Portrait of Elvie Thomas)

Knossos

Athinais Cultural Centre, Athens

4 October – 4 November 2004

Charles Howard has been painting on Skyros for more than thirty years.

On Skyros, things exist as universal Platonic forms, rather than as particulars. There is the universal version of a house (white, flat-roofed, with a carved wooden gallery inside), a miniature chair, a bed, a curtain. The design of these you feel has remained unchanged since time immemorial, though the materials might be new. Chapels shine white from the side of a hill or a rock in the sea; boats scout for fish. Because there is just one design for ach object, what you could call ‘choice anxiety’ is eliminated. This Platonic system of ideal objects is essential to the Greek island, where there is also only one Town, one Port, and one Airport. Here, Myth seems to flourish alongside the Greek Orthodox faith, its spirits lodging in familiar domestic objects, in the rocks, the trees, and the blue sea.

Aphrodite sits in her timeless universe on every patio, the mountain and the sea behind her. The curtain blows in the salt breeze and the sea merges its purple, velvety tone with the night sky. Aphrodite herself appears now alone, now with her lover or sister, now riding naked on one of the ancient Skyrian horses. You can trace her visual lineage from the hieratic art of Egypt and archaic Greece via Turkey and Persia to the present. Behind her, in the background, are tiny emblems of a timeless world: a star, a chapel, a bird, a cat, mountains, the town, the sea, a boat, a small aeroplane. The lover draws on a cigarette or dances beside a table on which sits the Platonic bottle of ouzo.

During the Renaissance, in order to paint a particular moment, when figures are in a particular place with the sun casting particular shadows, painters introduced perspective, the modelling of form, shadows and chiaroscuro. By returning to the pre-Renaissance principle, like Matisse, Charles Howard allows the moment to become timeless, eliding into the past, present and future. Freed from the constraints of this momentary realism, colours and their tones form surprising relationships: purple and brown; lime green, blue and red; delicious matt colour, like sun-faded walls and things lying in random juxtaposition on a table. Mountains become abstract zigzags, the pattern on a carpet or the orange and red lozenges of a ziggurat. Geometry and pattern are set against the youthful, organic shape of the figure or allowed to float in pure abstract form.

Charles Howard puts together in a painting his own vocabulary of imagery: a red sail and red lips, a blue moon and a blue coffee cup, a star and the collection of stars that make up the Town on the hill, the large and the small, the near and the far, all on the picture plane in a balanced composition that links personal memories with an ancient past.

Anne Harris, Royal Academy of Arts

4 October – 4 November 2004

Charles Howard has been painting on Skyros for more than thirty years.

On Skyros, things exist as universal Platonic forms, rather than as particulars. There is the universal version of a house (white, flat-roofed, with a carved wooden gallery inside), a miniature chair, a bed, a curtain. The design of these you feel has remained unchanged since time immemorial, though the materials might be new. Chapels shine white from the side of a hill or a rock in the sea; boats scout for fish. Because there is just one design for ach object, what you could call ‘choice anxiety’ is eliminated. This Platonic system of ideal objects is essential to the Greek island, where there is also only one Town, one Port, and one Airport. Here, Myth seems to flourish alongside the Greek Orthodox faith, its spirits lodging in familiar domestic objects, in the rocks, the trees, and the blue sea.

Aphrodite sits in her timeless universe on every patio, the mountain and the sea behind her. The curtain blows in the salt breeze and the sea merges its purple, velvety tone with the night sky. Aphrodite herself appears now alone, now with her lover or sister, now riding naked on one of the ancient Skyrian horses. You can trace her visual lineage from the hieratic art of Egypt and archaic Greece via Turkey and Persia to the present. Behind her, in the background, are tiny emblems of a timeless world: a star, a chapel, a bird, a cat, mountains, the town, the sea, a boat, a small aeroplane. The lover draws on a cigarette or dances beside a table on which sits the Platonic bottle of ouzo.

During the Renaissance, in order to paint a particular moment, when figures are in a particular place with the sun casting particular shadows, painters introduced perspective, the modelling of form, shadows and chiaroscuro. By returning to the pre-Renaissance principle, like Matisse, Charles Howard allows the moment to become timeless, eliding into the past, present and future. Freed from the constraints of this momentary realism, colours and their tones form surprising relationships: purple and brown; lime green, blue and red; delicious matt colour, like sun-faded walls and things lying in random juxtaposition on a table. Mountains become abstract zigzags, the pattern on a carpet or the orange and red lozenges of a ziggurat. Geometry and pattern are set against the youthful, organic shape of the figure or allowed to float in pure abstract form.

Charles Howard puts together in a painting his own vocabulary of imagery: a red sail and red lips, a blue moon and a blue coffee cup, a star and the collection of stars that make up the Town on the hill, the large and the small, the near and the far, all on the picture plane in a balanced composition that links personal memories with an ancient past.

Anne Harris, Royal Academy of Arts